HUNGARIAN COMFORT FOOD

A nourishing dumpling soup from Jeremy Salamon's new book, Second Generation (plus: a Q+A and video!)

Good Morning!

This is the last installment of our Hungarian Food Appreciation Week—lapping over a little from last week with a soup that is right on time for cold/flu season (we are a bit sniffly in this house!) and Rosh Hashanah for those who celebrate.

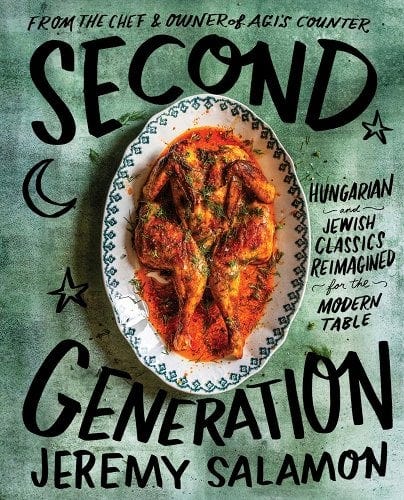

Today’s post is special because not only does it come with a Q+A with James Beard-nominated Hungarian-American chef Jeremy Salamon, owner of the beloved Agi's Counter in Brooklyn (a 2022 pick for Bon Appétit's Best New Restaurants)—but it also includes a video of Jeremy and I cooking together. Jeremy came to my kitchen last week during the peak of his book tour for his new book, Second Generation. The book is a revelation for Hungarian food enthusiasts because it’s the first of its kind (in English) for many years.

The real hero of our time together is this dumpling—currently floating in a super nourishing soup, but one that would be equally at home alongside Chicken Paprikas, Gulyás, or Jeremy’s Lamb Bocht. Below, find our Q+A, the recipe, and some cheeky videos of Jeremy and I cooking his soup together.

I’ll be back next week with pancakes and some other practical guides for fall cooking. For those who have deeply enjoyed this extra lean into Hungarian food and history, know that more is coming later this fall, including an updated Budapest Black Book, and some prized Hungarian recipes near the holidays.

xx

Sarah

Welcome!! ~ This is a reader supported publication. Upgrade to paid below for full access to full recipe archives, complete travel guides, essays and more. Now, there’s another bonus for going paid: you’ll have access to occasional video to accompany recipes, like the one below. ♡

READ MORE ABOUT HUNGARY:

Attention: It’s Chicken Paprikas Season

The Key To Mastering Goulash, the World’s Most Famous Stew

Q + A with Jeremy Salamon

Sarah: It’s wonderful to have you here. I’ve read every page of your book, and I loved reading all about your grandmothers–both are Jewish, and one of whom, Agi, is Hungarian. You talk about learning Hungarian flavors from your grandmother at her table in Florida. Can you share with us when she came to the US from Hungary?

Jeremy: Grandma Agi fled Hungary in 1956 via Vienna and came to Queens, NY, where she later opened a dry cleaning business with my grandfather, Pichu. They met at a Hungarian prom on the Upper East Side.

Sarah: Hungarian Prom! That is so charming; I want to go! After they left Queens for Florida, were there other Hungarians in her community? Or was it only Grandma Agi who connected you to Hungary?

Jeremy: My grandmother’s mother–my great-grandmother Cookie, also lived in Florida. They had good Hungarian friends from New York. In Florida, it was just Grandma Agi flipping her palacsinta with her bare hands, opening little Ferrero Rocher wrappers, and drinking coffee.

Sarah: Was Agi’s food super traditional Hungarian, or did it evolve before you came along?

Jeremy: Her version of Hungarian food was already distanced from Hungary. Because of what they went through* my grandfather never wanted to return to Hungary. He was very bitter about it. Her cooking was a way to preserve her heritage. She wanted to forget in a way but also not forget.

Sarah: Oh yes, the mood of the 56’ers (Hungarians who fled Hungary in 1956) was very complicated. They were not celebrating being Hungarian at that time.

*(a bit of history: The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 began with student protests and escalated into a violent armed insurrection against Soviet control. The 1956 Hungarian Refugee Crisis was the largest in Europe since World War II, with around 200,000 Hungarians fleeing the country.)

Sarah: Skipping forward a generation to your father, Agi’s son. Was Hungarian identity important to him? Did he cook Hungarian food or identify with Hungarian culture?

Jeremy: No, it wasn’t really important to him. I thought it was normal— like everyone had a grandma from Hungary. Foodwise, he maybe felt like that was his mom’s responsibility and not his.

Sarah: My husband is Hungarian, so my kids are first-generation Hungarian-Americans with strong ties to Hungary via grandparents and all their cousins still living there. Even though they’ve lived and gone to school in Hungary and have been to Hungary every summer, there was an age where each of them latched hard to their Hungarian culture—wanted to learn the language, eat only Hungarian food, etc. For my son, it was this summer—around age 9. For my daughter, it happened much earlier. Did you experience anything like that? Was there a particular age when you realized Hungarian culture was rare and special?

Jeremy: If it weren’t for my career in food and cooking, I don’t know if my interest in Hungarian culture would ever have evolved the way it did. I was in my late teens, living alone and going to culinary school. I remember the chefs I worked for encouraged me to explore my style. I didn’t know where to start. Everyone else started with their roots, and when I looked around, I saw that no one was cooking Hungarian cuisine in a way that I could understand as a young adult. Then, I started probing.

I started reaching out to family members on my father’s side who had much stronger ties to Hungary. Suddenly, I was invited to family gatherings—weddings, bar mitzvahs, family dinners—on my own. For a 20-year-old, it was a big experience.

A couple of years later, I realized the only way to understand it was to go there. So, I got a ticket to Hungary and stayed with my cousins for three to four months. My cousin Peter is a promoter for many of the big opera houses, so I got to see the very traditional side of Hungary with him. My cousin Feri took me out partying, and with him, I could see the much younger side of Budapest.

Sarah: How is your Magyar now?

Jeremy: What?

Sarah: Your Hungarian–language.

Jeremy: Oh right—obviously, not that great. (laughs)

Sarah: Let’s talk about the book. Many of the modifications you take on Hungarian classics (in the book and at Agi’s) make sense to me and are similar to how I modify Hungarian classics. Probably because of our background working in restaurants, it teaches you what liberties you can take and succeed.

I always feel that Hungary is a nation of innovators, and Hungarian cuisine–while very delicious even in its traditional forms–can also handle innovation. But many Hungarians are devoted to history and classics. Do you have customers or family members who misunderstand or criticize your recipes?

Jeremy: All the time. On the opening day of Agi’s counter, someone came to the door with their wife and baby and said: “That’s not Palacsinta; that’s not traditional Hungarian.”

Sarah: Ouch, opening day!

Jeremy: Yes. I remember when I was the chef at the Eddy when I started experimenting with Hungarian recipes more publicly. Someone asked for me to come into the dining room, in a packed 30-seat dining room, and I thought she was going to slap me in front of everyone. She said: “Your grandmother should be ashamed of you. This food is a disgrace!”

Sarah: It’s so hard! When I contribute Hungarian recipes to national magazines, some Hungarians criticize that it’s not the original or how their mother made it (even when I outwardly proclaim that it’s not intended to be THE classic). But then many people are so grateful to see their culture celebrated and admired in a serious way. They write to me and thank me. Those letters and notes mean so much.

Jeremy: I greatly respect you for putting those recipes in the New York Times and Saveur because you put yourself out there. Early on, seeing your work made me feel like there was room for food like mine.

Sarah: Thank you!

Jeremy: But yeah, people are crazy about their traditions. They are so intense. But I also admire, in this odd way, the pride behind it.

Sarah: Yes, me too. For example, my 13-year-old daughter, who has intense Hungarian pride, was worked up about the fact that there is a Ceasar salad in your book because even though it has caraway seed in it, and we know it’s going to be so delicious, she knows that Ceasar salad comes from Mexico. I just laughed. But it’s also sweet that she feels strongly about it despite mostly growing up in America.

Jeremy: Ha, yes! But we do have a lot of younger Hungarians who come in, and they get it. You don’t have to explain it to them. I’ve been thanked for taking it on and spreading the gospel of Hungarian cuisine.

Sarah: Switching gears a bit, your book's subtitle is Hungarian and Jewish Classic Reimagined for the Modern Table. Is it challenging for you or important to you to articulate to your audience how many classically Jewish foods are tied to Hungarian and other Central European cultures?

Jeremy: It’s a tough line to walk. My grandfather was quietly proud to be Jewish; he was a kind and wonderful man; he played the violin, he loved flowers. But he hated that the Hungarian leadership turned on the Jews during the war. It influenced my grandmother’s cooking and her willingness to adapt. I think my grandfather was so relieved to be in America that they embraced it fully–everything that came with it, including the food.

Sarah: Yes, I can imagine. Though my husband’s story is very different, there are some overlaps. He grew up in Hungary behind the Iron Curtain (under Russian occupation) in the 80s and 90s. He couldn’t leave the country until he was 15, so by the time he immigrated to the USA in his early 20s (also via Vienna), he embraced American culture: surfing, Coca-Cola, skateboarding, and American movies. I always joke that he is more American than me.

Sarah: Because of the pain, history, and layering of different cultures, there is such depth to Hungarian culture, so much to uncover and share. There’s so much beauty, but it’s also complicated.

Jeremy: It’s hard to wrap that up with a bow and present it in a digestible way to people who don’t know the details.

Sarah: Not an easy job. You’ve done well. Moving to this recipe, I’m drawn to this dumpling soup because both soup and dumplings are a big part of Hungarian culture. It has a hominess that reminds me of Matzo Ball Soup. Historically, Matzo ball soup is said to originate in the Ashkenazi community, influenced by the dumpling soups of Eastern and Central Europe. To you, is this soup Jewish, or Hungarian, or both? Do those distinctions matter?

Jeremy: It is both. Agi made these semolina dumplings, but she made hers super big. These are floating in a flavorful chicken broth, but they could also be served alongside all kinds of braised meats.

Sarah: András mother makes incredible dumplings. I imagine them with mushroom guylas, quick chicken paprikas, and your Unfaithful Chicken Paprikas on the cover of your book, which I hope people get to taste—it’s gorgeous. I feel like that’s the perfect October dinner, with a glass of Egri Bikavér (Hungarian “bull’s blood”) red wine.

Sarah: Regarding the book, are there recipes you left on the cutting room floor that you still think about?

Jeremy: Oh yes, Flodni. I can make it. But I didn’t feel confident enough in the recipe to publish it. I’m not a pastry chef (Our opening pastry chef designed a lot of the recipes in the book). I really wanted to figure out the Flodni, but every time I made it, I couldn’t get it to fruition. I told someone recently that it’s something you need to experience in Hungary made by the right person.

Sarah: Last question: How is Agi now? Is that her I see in your book (p. 116)? She’s so elegant!

Jeremy: Yes, Agi still lives in South Florida in her apartment. She is 97 or 98 and has pretty severe dementia.

Sarah: I’m sorry to hear that. Will you be able to bring her the book and show her, even if she doesn’t understand completely the gravitas of this moment for you?

Jeremy: Yes, I plan on bringing this down to her. When I told her I was opening a restaurant with her name on it, I brought her the Agi’s Counter baseball cap and said, “You’re going to be famous.”

She said, “Tati, I’m already famous.” She believes she lives in a five-star hotel above Bloomingdales, who put her whole closet together, and that she gets croissants served to her upstairs every morning.

Sarah: Such a beautiful image. There’s something very elegant about Hungarian women. Even though there are so many salt-of-the-earth, humble people in Hungary, there is also a great history of fashion, high culture, and opulence. So much was buried under the rubble of war. But then you have characters like Zsa Zsa Gabor, and you see it.

Jeremy: Agi was always very Zsa Zsa Gabor-esque, with leopard prints and big baubles and beads.

Sarah: That’s the Hungarian grandmother I’m going to be one day!

Jeremy: I wish that for you!

THANK YOU, JEREMY! JUMP TO THE RECIPE, BELOW.

THE RECIPE:

Radish Soup with Semolina Dumplings

From SECOND GENERATION by Jeremy Salamon. Copyright © 2024 by Jeremy Salamon. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

This is a dumpling recipe disguised as a soup. These dumplings can easily hop pots, starring in chicken soup, or just simmer until puffy and served alongside Gulyás. I came up with this particular soup because I wanted a way to highlight the dumplings themselves in a fresh delicate stock. The radishes and their greens have a mild peppery flavor that soaks into the dumplings as they simmer for a perfect bowl.

Serves 4